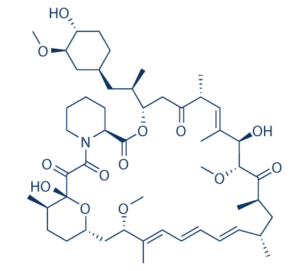

The aging research world was rocked in 2009 when a study showed that giving old mice a drug called rapamycin could significantly extend their lifespan1. It was quite remarkable because it was the first demonstration that aged animals could still undergo beneficial aging interventions. Before 2009, most researchers assumed aging interventions had to start at a young age.

Since then, a lot of studies have followed, and rapamycin, the canonical ‘mTOR inhibitor,’ has been shown to extend lifespan in at least fourteen other studies, confirming the late-age treatments, showing lifespan extension in both males and females, and in various different mouse strains2. Not only that, rapamycin has been shown to extend lifespan in cancer disease mouse models, and mouse models of progeria and mitochondrial dysfunction2. And the list doesn’t stop there, rapamycin has been shown to have benefits in other mouse models, including those of heart diseases, infections, and for neurological conditions including alzhiemer’s, parkinson’s and huntington’s diseases2.

So what’s the catch—why aren’t older people all taking rapamycin?

There are two catches: For one—and a very important one—these studies are all in mice, not humans. What holds for mice often doesn’t hold for humans. The second catch is that rapamycin unfortunately has a negative connotation, since it’s an FDA approved drug for use as an immune suppressor to allow organ transplantations. You wouldn’t want to willingly take an immune suppressor while you age, a time when your immune system is getting more and more vulnerable. But the fact is, rapamycin should better be labeled ‘immune modifier’ rather than ‘immune suppressor’. In 2014, a study funded by Novartis demonstrated that mTOR inhibition (with their own inhibitor, ‘RAD001’) in the elderly population actually boosted the immune system, demonstrated by a ~20% improved response to the influenza vaccine3.

So the fear of rapamycin compromising the immune system if given to the elderly was only that: a fear. So what about catch number one, that we mainly know what rapamycin does in mice? There are far less data in humans on rapamycin for aging. Though that hasn’t stopped people from taking it (see the MensHealth article here), and some early-adopting clinicians from prescribing it for off-label ‘aging’ use (see a rapamycin clinic here).

Formulations in humans designed for healthy longevity involve much lower doses than given for immune suppression, e.g. a ~5mg dose weekly to slow aging, instead of the ~2mg dose daily that’s used in immune suppression. This dosing to ‘slow aging’ in humans is of course anecdotal information, though recently scientists have begun to actually explore this option. In 2018, one study with aged (70-95 years old) but otherwise healthy people found that treatment of a 1mg daily dose of rapamycin for eight weeks was safely tolerated (no negative changes in a variety of clinical markers or self-perceived health)4. And very recently, in May 2021, a phase IIB and phase III clinical trial sponsored in part by resTORbio, a pharmaceutical company aimed at designing mTOR inhibitors to target aging, reported results on their own proprietary mTOR inhibitor RTB101, where they found no adverse effects after 16 weeks of treatment in the 65+ population they followed during the flu season. They also didn’t note any positive effects in their primary endpoint though either (reduced total respiratory tract infections), but found gene expression patterns that would suggest increased immune function occurring in the more compromised elderly and a significant reduction of severe respiratory tract infections5. In any case, it’s all a very promising start.

So the bottom line to the question, should I take rapamycin to slow my aging, is this: (1) Lifespan benefits in mice seem to be equal when rapamycin is fed to young or already aged mice, so if you are not old, put the idea on the backburner for now. (2) If you are old, then consulting a physician is a prerequisite before taking any drugs: rapamycin’s side effects are known to include ulcers of mouth and lips, hyperglycemia/diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypercholesterolemia, to name the common ones. In line with that, it’s important to note that we (‘science’) are close but we aren’t there yet: more clinical trials are needed to study rapamycin in aging humans. So the advice is: live healthy and hang in there.