The answer is pretty simple, and I’ll try to outline it in just a few steps.

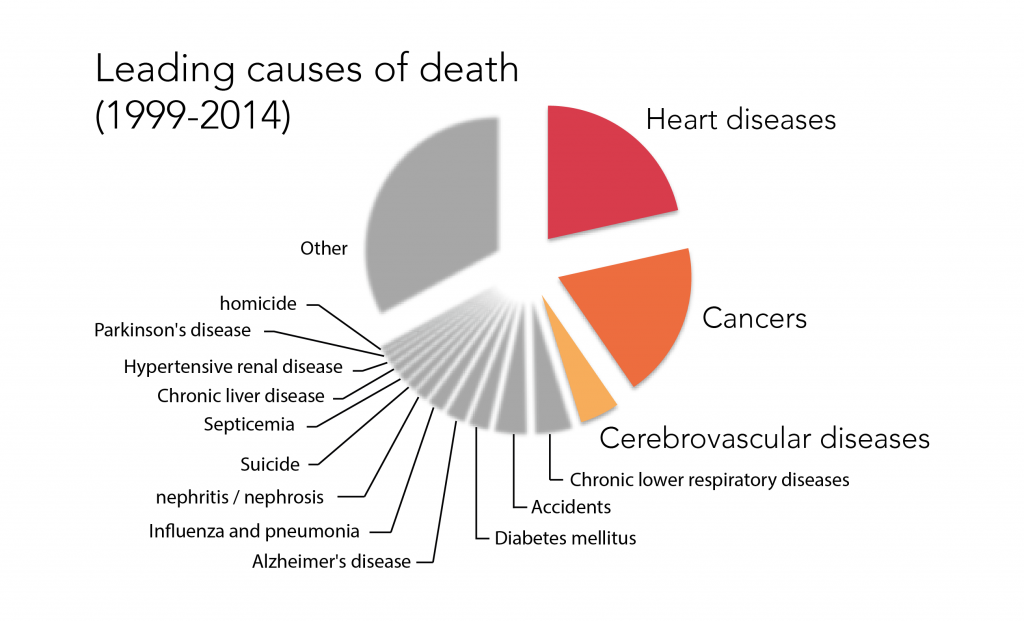

1) If we go to the CDC website (centers for disease control and prevention) and download death counts for the top 15 causes of death, we can plot the resulting %s as a pie chart, and see right away what’s going on in the US. For example, the top three causes of death can be classified as heart diseases, cancers, and cerebrovascular diseases (i.e. strokes).

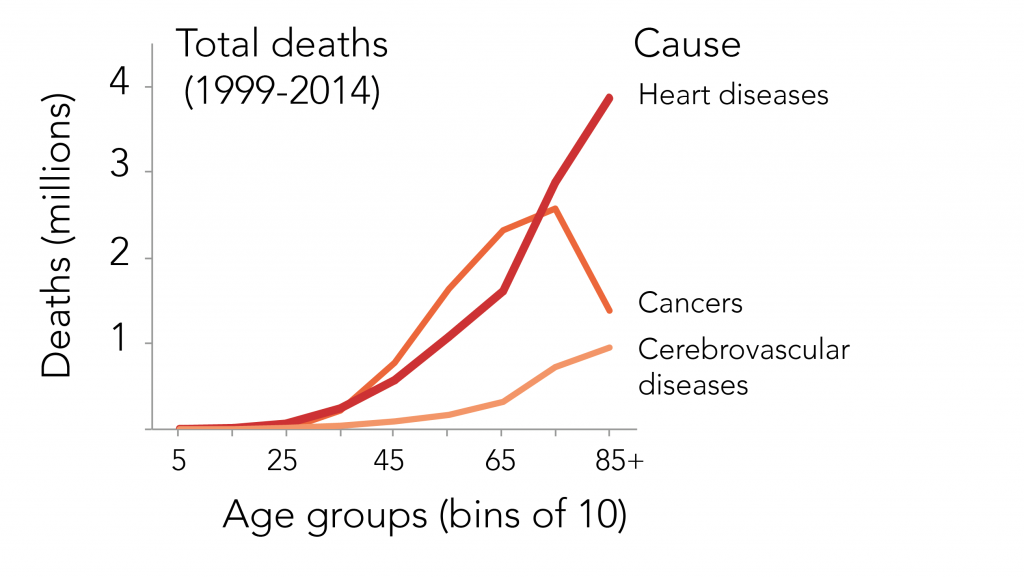

2) Still enjoying the diversity of data that the CDC offers, we can then look at how these top three causes of death occur at different ages. We plot the amount of deaths present at each age, and we see something that you might say is obvious; there are more and more deaths from these diseases occurring as the age groups get older. This is why we generally call these ‘age-related’ diseases. In fact, many others on the top 15 list also fall under this category, i.e. diabetes, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, etc. Side note: for a very nice visualization of the causes of death and their occurrences at different ages, I highly recommend exploring this blog’s illustration.

3) In brief, the top causes of death in the US go up in prevalence the older we get. This is directly linked to the fact that our bodies age. Our ‘youthfulness’ diminishes over time, and our bodies change in such a way that diseases manifest themselves. The results are diseases and then death.

There are options though.

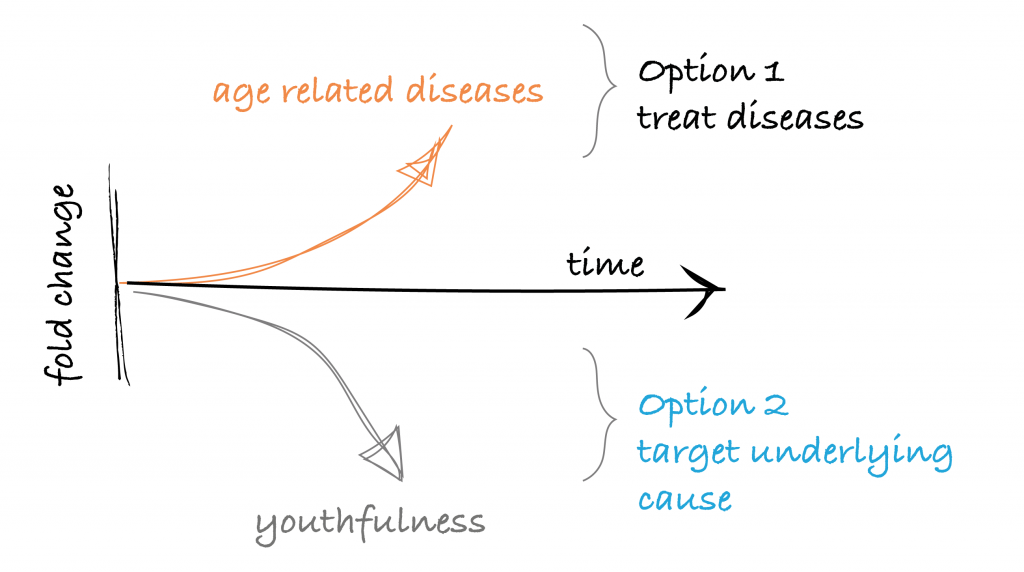

Treating the resulting diseases, or targeting their cause (aging)

Having the current situation, we have a few options now. The historic and most popular approach has been to develop medicines for each disease. If you have cancer, you get treatments for cancer. If you have a disease, for example, in your coronary artery, you might have a heart bypass surgery. If you have diabetes, you get diabetes medicine. This is in fact ‘modern medicine’, and is, nonetheless, something we should be extremely proud of as a species for having developed. These feats involve quite some impressive technologies, skills, and mountains of research-years. Another option though, which is complimentary, would be to target the underlying problem that is causing all of these diseases. In this case, we would make medicines that would target… aging.

The hypothesis would be that these diseases occur in part because our bodies get older, so we should try to make that happen less. Various scenarios could follow.

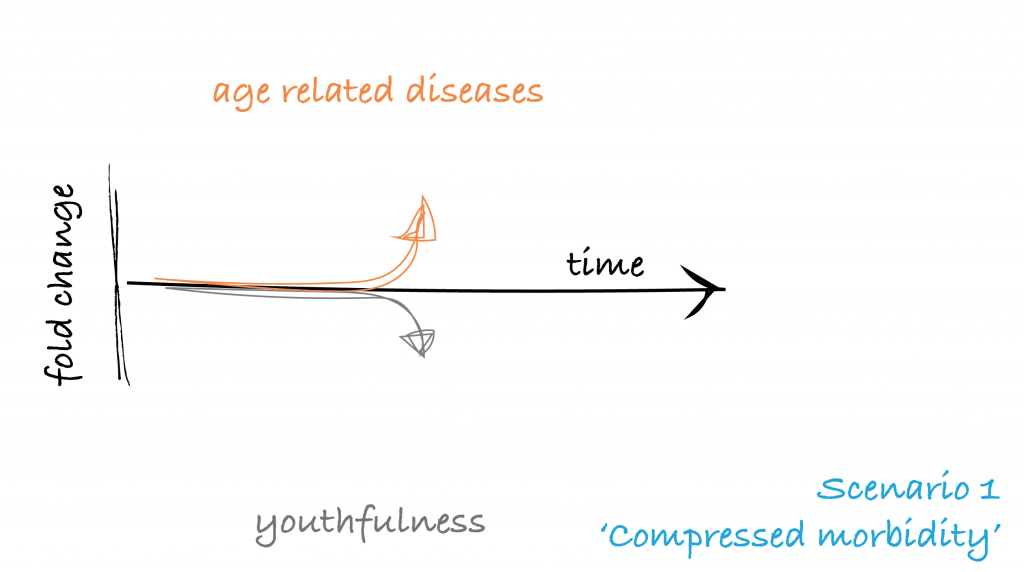

Scenario 1 | Compressed morbidity

The first would be that we would end up having the same lifespan as we currently have, but we would maintain health and (more or less) youthfulness until the end, and diseases would occur only at the very end of our lives. This would be what we call ‘compressed morbidity’.

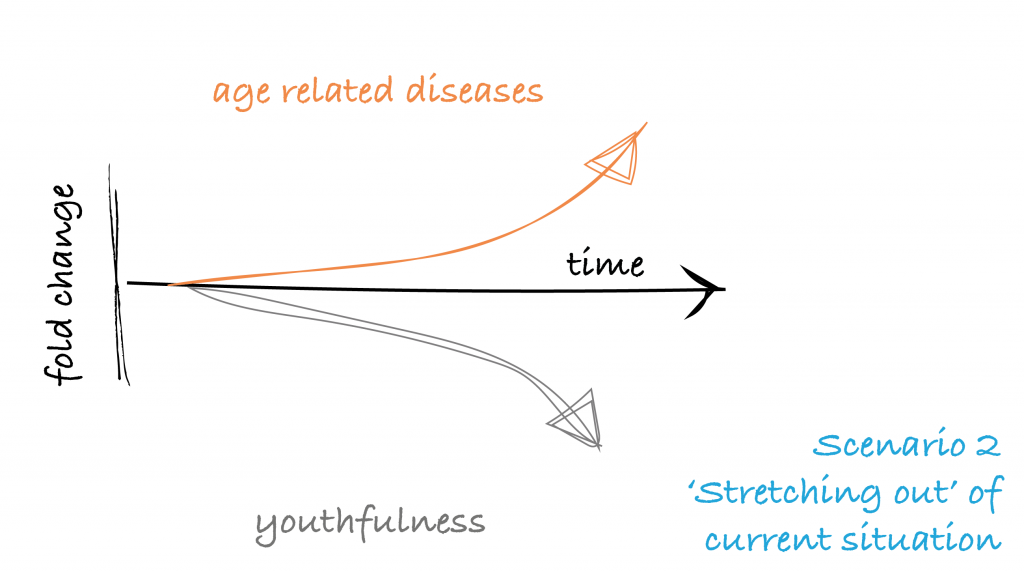

Scenario 2 | Stretch out

The second scenario is that we would ‘stretch out’ the current situation. We would live longer, but the ratio of health-to-disease that we have in our lives would remain the same. This is why we would say that medicines that target aging would be ‘complementary’ to modern medicine that target diseases. We may still need it after all.

Probable result | Both

In fact, the most likely situation that would occur is something in between these two scenarios. While trying to achieve ‘compressed morbidity’ in our lifespans by using medicines that target aging, we would also end up living a bit longer, though with a better ratio of health-to-disease.

The testing of these medicines, termed ‘geroprotectors’, is in fact already underway in humans, as just last year the FDA approved such a clinical trial (read about the TAME study here). Indeed we are already at the start of developing medicines that target the underlying cause of many diseases, aging, and at the start of being able to prevent these diseases before they even emerge. But, it’s only a start…