The next time you poop, take a moment to realize that you have become more human by doing so. Sure, you have gotten rid of some smelly ‘uncivilized’ stuff, but at the same time, a large amount of little buggers have vacated your gut. Since these little buggers live in and on our bodies in about a 1:1 ratio with our own cells1, simply by pooping some out, you have tipped the scale to being slightly more ‘human’. Those little buggers are bacteria, and constitute what scientists call the ‘microbiome’. It’s a thing that (some) scientists love to dig in to, sequencing your poop to find out what types of bacteria live there. These bacteria are involved in the breakdown of food and the production of vitamins, so their impact can be vast. There seem to be good guys and bad guys, but how important is it all?

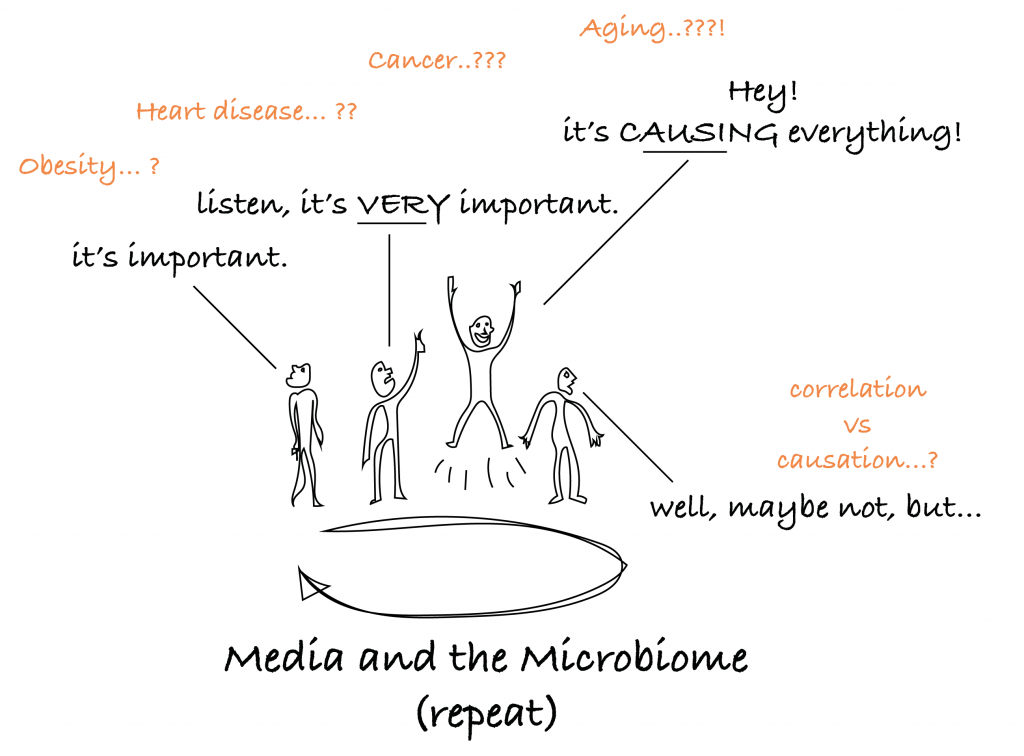

And that is the typical cycle that the media goes through regarding the gut microbiome.

So what can we really say about it?

This much is true: changes in the gut microbiome’s composition correlate with a lot of things, astonishingly so. This includes; obesity2, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)3, colon cancer4, cardiovascular disease (CVD)5, inflammation6, frailty7, your diet8, and our favorite; aging9–13. And more correlations keep popping up.

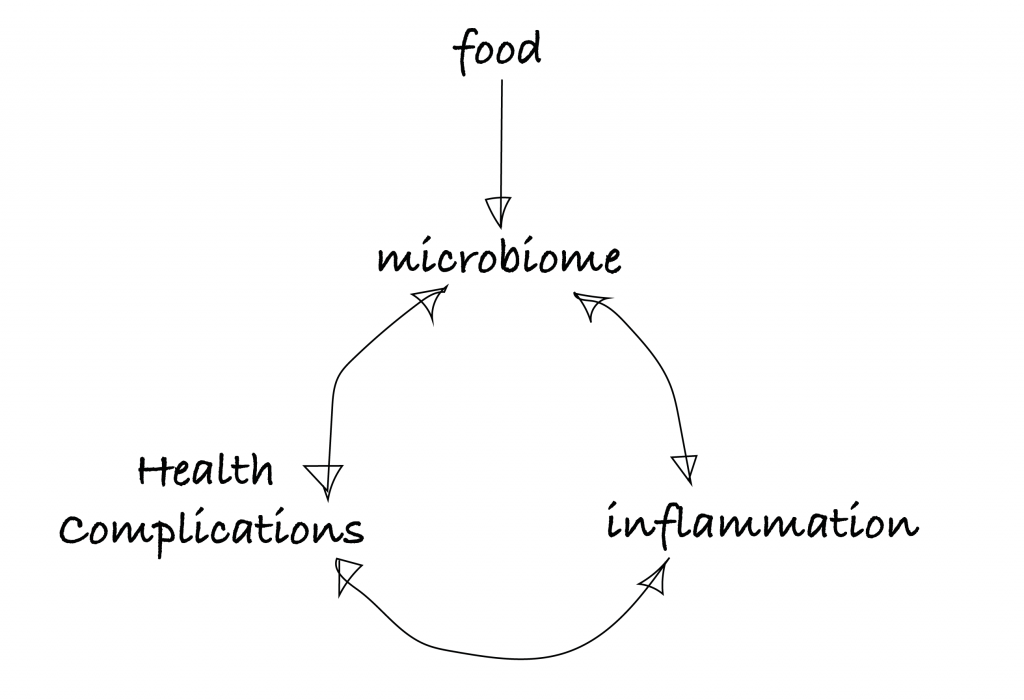

That’s why the media has a field day about it. But what we are left with is the typical problem of not really being able to tell the difference between correlation and causation. But correlation is definitely there, and causation feels temptingly close, so an overview model with arrows pointing in every direction might look like this:

What’s the relation to aging?

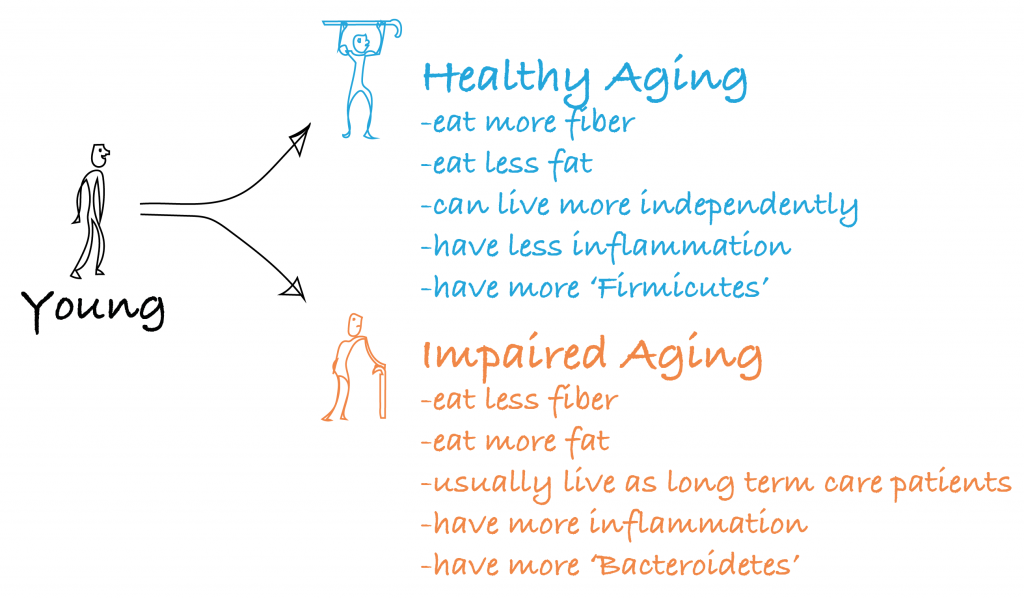

It is undeniable that the microbiome changes with age. Of the two major groups (phyla) of little buggers in your gut, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes9, it has been shown that a skewing occurs towards having more Bacteroidetes with age10. What’s more, it is also shown that having more of that group is correlated to having more frailty and impaired function with age6. We know that the microbiome correlates with the food we eat8, and indeed, healthy aging individuals (i.e. less frailty, more Firmicutes) seem to eat foods with more fiber and less fat content than their unhealthier aged peers6. Here is a drawing summarizing the literature6,10–12:

What’s more, interventions in mice that extend lifespan, such as dietary restriction14, and feeding the drug Rapamycin15 (one of the most promising interventions to delay aging), also impact the gut microbiome. So the picture is getting pretty clear, the microbiome is heavily implicated in aging, healthy aging, and longevity. So let’s use it to take back lost youth! So are the Bacteroidetes the bad guys?

Here is why it’s more complicated.

Those are all correlations. It’s not clear if aging causes our microbiota to change as described, or vice versa. Furthermore, when thinking about how to use these little buggers as therapies, one thing to keep in mind is that the composition of bacteria changes throughout the length of the gut. Most research is just based on sequencing the end product, poop, which is thought to mainly reflect the composition of bacteria in one section (the distal colon)12. This makes it hard to say what the ‘best’ bacteria might be for us (it could be different throughout the gut). On top of that, there are thought to be over 600 genera of bacteria existing in the gut16, with at least 1000 – 1200 species possible, and any individual may be having at least 160 of these17. Remember, the way scientists categorize a species is with the following hierarchy: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species. So the Bacteroidetes ‘phylum’ actually includes a lot of different species. So while the above aging research painted a picture of Bacteroidetes as being bad, this phylum has been shown to be actually less present in obese mice18, and obese humans2,19 though even these findings can’t always be replicated, illustrating the fact that scientists are still at the start of figuring out how our microbiome influences everything. The science is simply at a very early stage of understanding for how to actually use bacteria to influence our health in aging.

The bottom line: What can you actually do about it to benefit your health?

Your microbiome is related to chronic inflammation and health complications, and those are related to aging. So let’s try to keep it in check. Here’s what I would recommend doing:

- Fiber. Eat it. It’s the recurring theme, linking health to the microbiome. So eat foods with fiber (i.e. broccoli, carrots, cabbage, celery, courgette, eggplant, kale, pumpkins, turnips… those will do the trick, but the list goes on).

- Yoghurt… why not eat it? Or something else with live bacteria, such as kefir or cultured vegetables (i.e. sauerkraut or kimchi).

That’s it for now.

Ok. I’m sorry to have disappointed you, you have read through this whole blog just to have been left with a simple recommendation, to eat fiber, and a not-so-affirmative recommendation to eat yoghurt, where the yoghurt part was already suggested over 100 years ago by nobel prize winner Élie Metchnikoff20. But that’s where we stand with things. If you want some more entertainment around the microbiota hype though, you might want to read about the rises and crashes of microbiome based therapeutics companies, or a story on how a scientist has injected himself with the stool of a hunter-gatherer. You might also be interested in seeing perhaps the most promising direction for microbiome research: personalized nutrition21.

In any case, go eat that fiber.